This scribe was obviously not enjoying their work. Thus, let this composition be ended here. In Aelfric’s 11th-century Old English De termporibus anni, a concise handbook of natural science, the scribe finishes with:

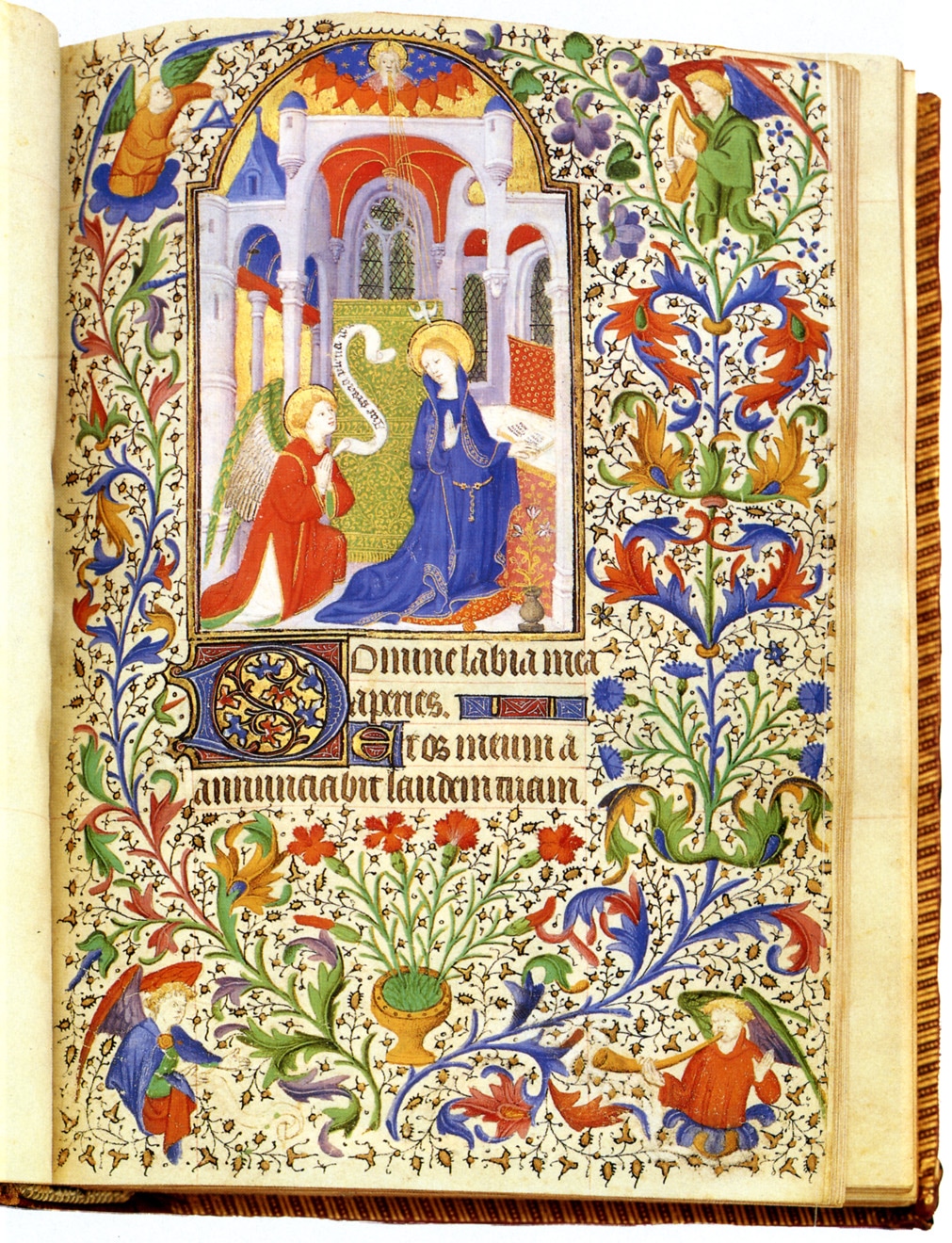

Sometimes, though, the scribes were a little bit bolder and wrote more emotively about their work. The scribe has written the Latin words “ Probatio Penne”, which means “pen test”. vi, which is currently held in the British Library in London. We see this in a manuscript catalogued as Cotton Vespasian D. These types of doodles – an odd name here and there, modest works of art or even a line of music – are important because they give us a rare glimpse into the real day-to-day life of these medieval scribes and what they really thought about the books they were scribing. Now, though, with modern technology, medievalists can uncover all sorts of messages that lie behind the pages of these ancient books. When we see images of scribes (people who made written copies of documents) writing, they are often depicted with a pen and knife in hand.ĭrawings in the Book of Hours. The origins of doodling in the Middle Ages are hard to pinpoint, but they probably started with pen trials.

Given the skills and specialisation required for writing in the Middle Ages – the training, level of literacy, access to materials, for example – doodles in manuscripts were rarely thoughtless or accidental. It was commonplace to write in margins, underline and annotate, use blank spaces for recipes and handwriting practice, and even colour in images. Usually found in the flyleaves or margins, doodles can often give medievalists (specialists in medieval history and culture) important insights into how people in earlier centuries understood and reacted to the narrative on the page. Scribbling haphazard words, squiggly lines and mini-drawings, however, is a much older practice and its presence in books tells us a lot about how people engaged with literature in the past.Īlthough you wouldn’t dare doodle on a medieval manuscript today, squiggly lines (sometimes resembling fish or even elongated people), mini-drawings (a knight fighting a snail, for instance), and random objects appear quite often in medieval books. To “doodle” means to draw or scrawl aimlessly, and the history of the word goes back to the early 20th century.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)